Susan Hawthorne presents Lesbian: Politics, Culture, Existence at FiLiA

Susan Hawthorne author Lesbian: Politics, Culture, Existence

Radical Feminist Voices: Spinifex Press Panel 1, FiLiA, Brighton UK, 12 October 2025

https://www.spinifexpress.com.au/shop/p/9781922964120

I respectfully acknowledge the wisdom of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and their custodianship of the lands and waterways. The Country on which I live and work is Djiru.

I also acknowledge the many women throughout history who have fought for women’s freedom and the freedom of lesbians, often at the cost of their lives.

My talk today centres on my book Lesbian: Politics, culture, existence (2024). I’m going to begin by speaking about some of the political issues I cover, but most of my talk will focus on the culture part, without which we would have very boring lives.

Politics

I’ve been actively involved in the Women’s Liberation Movement since 1973, I’d read Germaine Greer’s The Female Eunuch in 1972, but it wasn’t until I joined the Women’s Liberation Group at La Trobe University that I found a way to do anything. I quickly painted posters and graffitied sexist advertisements. By 1976, I was writing a critique of heterosexuality as an institution, lesbian feminism as a political strategy and in defence of separatism (2019). I was still learning to be a writer so there is a longish gap before you get to my 1991 essay on sexual ethics, including BDSM, consent, and the defence of torture as sexual play. I come back to this in a later essay from 2005 in which I respond to feminists arguing in favour of such dubious practices. In 2003, I became very concerned by the depoliticisation of lesbian culture and I try to write my way into a more positive space, that of the culture produced by lesbians.

In 2003, I embarked on a long research process on the torture of lesbians. It began after attending the World Women’s Congress in Kampala, Uganda. After a session on radical feminism in Africa, where I had asked a question about lesbians, a woman approached me and said, “Be careful, Be very careful. In Uganda they torture lesbians.” I was shocked, as I had never heard anyone speak about this. I read anything and everything I could find. There wasn’t much and lesbians + torture brought up pornography. Eventually I wrote an essay ‘Ancient Hatred and its Contemporary Manifestations: The torture of lesbians’. The material I read, the experiences that lesbians from many countries shared, was horrifying. I especially recommend the essay by Consuelo Rivera-Fuentes and Lynda Burke (2001) ‘Talking With/In Pain: Reflections on bodies under torture’ WSIF. Consuelo spoke at FiLiA in 2019. It was a powerful speech about what happened to her under the Pinochet regime in Chile and anyone who was there left the room shaken. Sadly, Consuelo died in 2023 and FiLiA held a tribute for her at the Glasgow conference. This is what she wrote in 2001:

… no training session prepared me for this intense pain … my pain … the one I did not choose … all this alienation, this empty vacuum …, my body, my mind, my pain … this is not happening … I am a little speck in the universe … which universe? … the world is not anymore … I am … disintegrating … bit by bit … yell by yell … electrode by electrode … The pain … all this pain here and there, down there in my vagina … the agony … where am I? Where is my I? (Rivera-Fuentes and Birke 2001, p. 655; italics and ellipses in the original).

“Where is my I?” asks Consuelo Rivera-Fuentes after her experience of torture. She is also asking where is my lesbian I? Where is the centrality of the experiences of lesbians recorded and recognised? Where is the recognition that the violation of lesbians goes on day after day, and no one speaks of it.

Since 2003, I have written a lot of essays about the situation of lesbians internationally: violence, torture and murder and also about the huge difficulty lesbians face as refugees. An example: for Nigerian activist, Aderonke Apata, it took 13 years to gain asylum in the UK. One of the sticking points, according to Theresa May, who headed the Home Office at the time, was that Aderonke was pretending to be a lesbian to gain asylum. She was put in solitary confinement for a week in Yarl’s Wood Immigration Removal Centre in 2012. The accusation of pretence was because she was the mother of a child, and the assumption was, therefore, she must be heterosexual. Some lesbians have married because this was a temporary protection for them, or they were forcibly married.

In the last year, as part of the Coalition of Activist Lesbians (CoAL), three of us members have been working on a project called The Lesbian Tent (The title comes from the 1995 Fourth World ‘s Women Conference in Beijing. At this conference, a tent was set up where women could meet and discuss issues of importance to lesbians.) Through The Lesbian Tent Project we have been working with two lesbians from Africa, assisting them in their application for refugee asylum in Australia. This has been one of the hardest activist projects I have ever been involved in. We are told that it could take six years, even for an emergency application. There is despair, anxiety and a lot of waiting.

Culture

I now want to talk about lesbian culture. As I write in one of the poems towards the end of my poetry collection Cow (2011).

“who says that we should be the only people on earth

without stories” (p. 154)

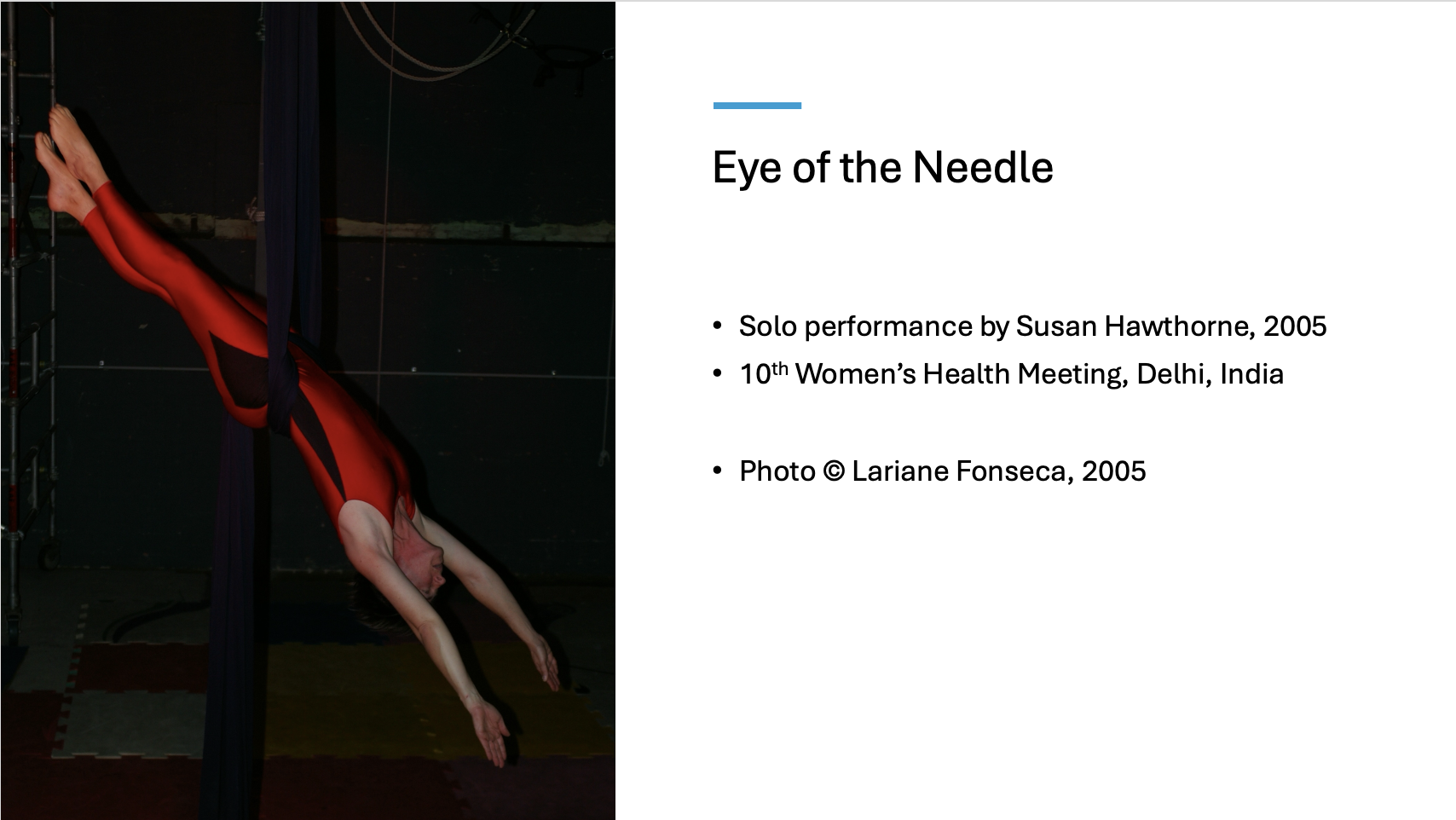

This is a pertinent question, given that when one speaks of women’s culture – and especially of lesbian culture – the usual response is puzzlement, silence and disbelief. I have been participating in lesbian culture since the 1970s. My main areas of engagement have been circus (as an aerialist and acrobat) and literature, especially poetry.

In 2007, I wrote an essay ‘The Aerial Lesbian Body: The politics of physical expression’ (published in Trivia magazine). Near the beginning, I write:

Let me speak of my body. It is female. It is white (so-called). These things are easy to spot. It is older than it looks. It is a lesbian body. Visible to those who know how to pick up the signs. It is sometimes a body afflicted with a disability. A disability that ranges from completely invisible to highly visible. It is a body changed by epilepsy. It is a body breaking silences, crying out for speech. It is also a body that has explored the experiences of other bodies. Bodies not my own.

I joined the Performing Older Women’s Circus (POW) aged 42 (you had to be at least 40 to join). Over an eight-year period, I wrote scripts and developed aerials sequences on trapeze, cloud-swing, rope and tissue (also called silks), as well as acrobatic and acrobalance floor work. The areas we explored included the female body, the lesbian body, the aging body, the falling body, the disabled body, the speechless body, the tortured body and the singing body. Emotionally, we traversed the landscape of terror and joy.

After attending a circus festival where I spent six hours a day doing aerials – swinging trapeze – in this instance. I reflected on this:

I overcome the fear and drop. I don’t do it very well, but I do it. Then, in a move that is difficult at first, I am moving between sitting and standing on the bar. In that moment I lift, almost a bounce, from sitting and without warning comes a sense of weightlessness. I am child, I am bird, I am a woman in flight, and everything is in tune. The exhilaration lasts for days.

The exhilaration of aerials is akin to the exhilaration I have experienced when coming into contact with lesbian culture and when researching and writing lesbian poetry. Imagine being able to say: ‘All history is the history of lesbians.’ But you might notice that for many generations the sentence ‘All history is the history of man – or of men’s progress – or of men’s ideas.’ Such sentences are readily believed. It’s good sometimes to challenge yourself and others and to think differently. Monique Wittig in her novel The Guérillères (published in 1969 in French, and in 1971 in English) challenged the world. She wrote:

There was a time when you were not a slave, remember that. You walked alone, full of laughter, you bathed bare-bellied. You say you have lost all recollection of it remember … You say there are no words to describe this time, you say it does not exist. But remember. Make an effort to remember. Or, failing that, invent.

–Monique Wittig, The Guérillères, 1972

I have taken her exhortation ‘Or, failing that, invent’ seriously. I mentioned my book Cow before.

I wrote Cow on a residency in Chennai in 2009. I applied for funding three times. In the first application, I mentioned lesbians and sexuality; in the second women; the third time round I wrote only of cows – and succeeded. What the assessment panel didn’t know was that I was using the word cow as code for lesbian. Gertrude Stein when writing about Alice Toklas having an orgasm wrote, ‘Alice has a cow’. Suniti Namjoshi has a book called Conversations with Cow which follows the conversations had by a lesbian with an every-day lesbian separatist cow called Bhadravati. Wittig also wrote The Lesbian Body (1973 in French; 1975 in English). By this time, I had also followed the etymology of the word ‘cow’ which comes from the Sanskrit word ‘gau’ via Old Norse ‘kvinna’ connected to woman and queen. And to ‘gyne’ in Greek. Queen Guinevere is a linguistic descendant of all those words as is the word ‘queen’.

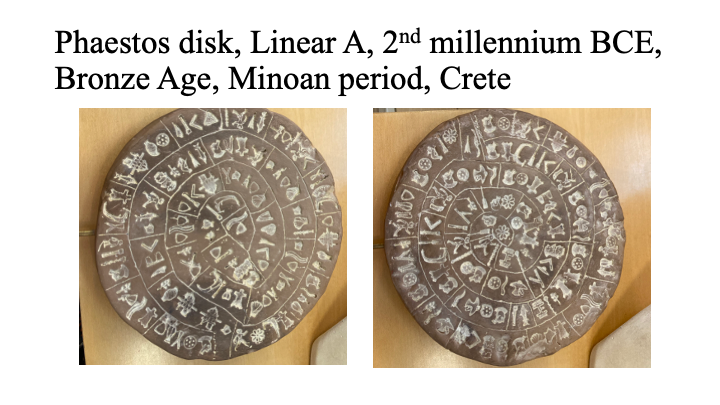

The quotation from Monique Wittig was at the centre of my thinking in 2013, when I got another residency, this time in Rome. Her ‘Or, failing that, invent’ dictum gave me permission to madly invent. I invented a whole lot of ‘lost texts’ from 300,000 years to the present. Some like the Linear A: Twenty-seven wethers, is based on partial decipherment of some of the characters on the Phaestos disk. As a farm-grown woman, I make a joke about the 27 wethers (castrated sheep) that the shepherdesses bring down from the hills. In poetry, you can do anything. You can make up worlds. But I am also serious. I am using genuine archaeological research and building new interpretations.

For me, the Phaestos disk represents the undecipherability of lesbian existence. Australian poet, Dorothy Porter summarises this nicely in a poem in her collection Crete (1996):

When I was twenty-two

just about everything

was Linear A (1996, p. 6)

Archaeology and inventiveness also lie at the base of artist Suzanne Bellamy whose sculpture, prints and other artworks are held in lesbian households across Australia, and she is also known in the US and Europe as a Woolf and Stein scholar.

In July 1979, I heard Suzanne Bellamy’s voice on the radio, she was speaking about the writings of Virginia Woolf. I was stuck to the radio and returned the following week for part two. In 1981, I finally met Suzanne at the Women, Patriarchy and the Future Forum in Melbourne. Soon after, I was travelling to Sydney to hear Mary Daly speak about her book Gyn/Ecology and interview her for radio.

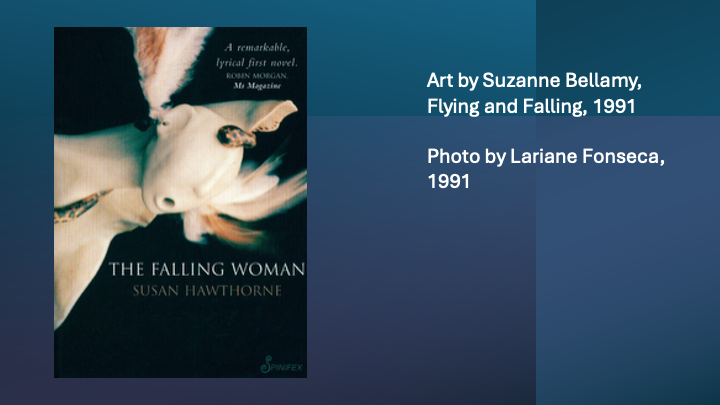

Meeting with Suzanne Bellamy was a key event in my life. The paper she gave at the Third Women and Labour Conference in Adelaide, inspired some parts of what was to become my first novel, The Falling Woman (1992).

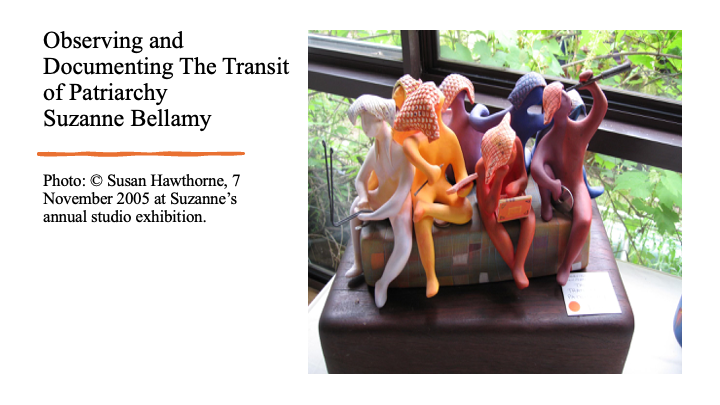

But more than that, I came to know Suzanne’s art, her extraordinary sculptures of native animals and soon her creative riffs on women’s prehistory. Her knowledge of archaeology, her long view of feminist resistance (she has a sculpture called ‘Observing and Documenting the Transit of Patriarchy’, as if patriarchy might be just a blip in human existence.

Suzanne said that archaeology depends on material evidence and much of that is fired pottery from thousands of years ago. Suzanne was determined that her work would last. She said of her work that she was

… looking for a new language to discuss the work of women in non-verbal creative areas – not only sculpture but all the nonverbal forms, all form (and of course by extension a new way of using words themselves) (Bellamy 1984, Australia for Women: Travel and Culture.

Before I move on to literature, I have a short clip of Suzanne speaking at the National Library of Australia Canberra in 2013.

The Lost Culture of Women’s Liberation by Suzanne Bellamy, National Library of Australia, 2013. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UC4w4Hnw5QI

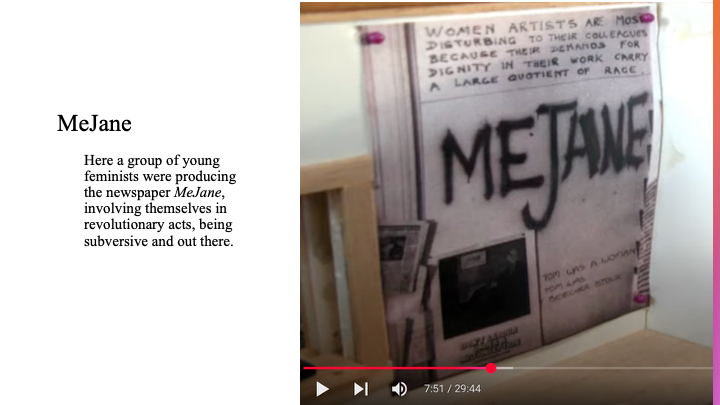

The clip begins just after Suzanne has explained that all their publications were authorised by Vera Figner, a Russian revolutionary of the late nineteenth century. If anyone was arrested, her name was Vera Figner.

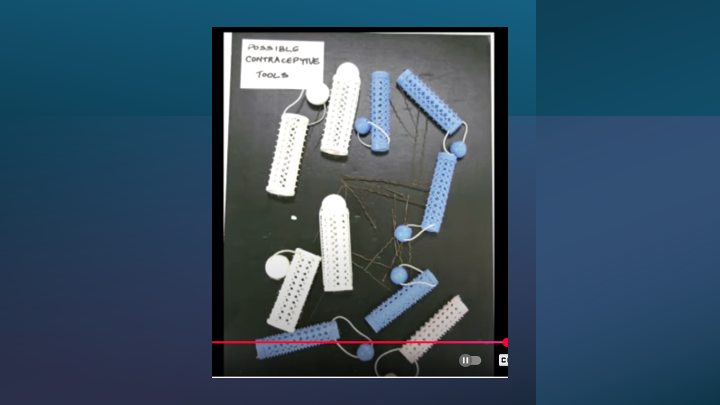

Among the remains were these which archaeologists of the time ventured that these might be some kind of contraceptive device.

For those of us who are old enough the previous slide shows the hair curlers we were expected to wear to bed overnight so our hair would be curled by morning. Not my hair! It didn’t work.

Boat: We hid our secret knowledge even from ourselves. Suzanne asks, What do you do when you have to save your culture?

This is a boat filled with women, sailing into exile. It is the position radical feminists and lesbians are in right now, when the word women is perverted; the word lesbian is considered trans phobic. Suzanne also says that these women are, “sailing upon the Sea of Amnesia”. The sculpture is placed on a painted canvas.

I suggest as many of you as possible should watch the YouTube link to Suzanne’s video the https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UC4w4Hnw5QI

Existence

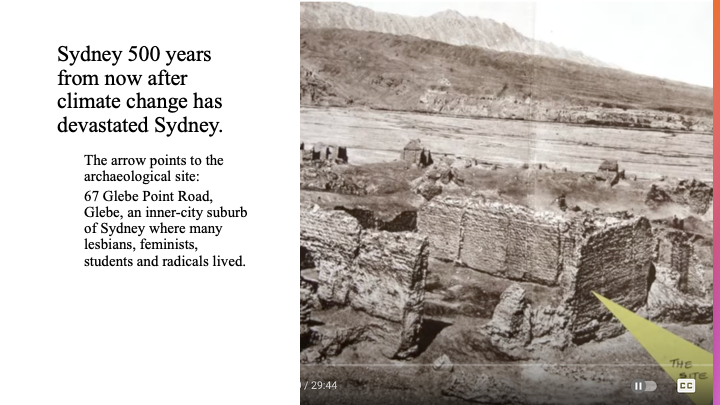

I want to finish with an extract from my novel Dark Matters (2017) which brings together politics and culture. It is about recognising the existence of lesbians; the awful violence that is done against lesbians and why we need a vibrant lesbian culture in order to keep our political activism going.

I cry. I cry for all. For all the women. For all the lesbians. I cry because no one cries for us. In Kampala and Chicago. We are shot and raped. We are thrown from the top floor of a high building in Teheran and Mecca. When they arrest us, they put us in cells with violent men who think nothing of having their own ‘fun’. In Melbourne and on the Gold Coast, we are tossed from cars, rolled into a ditch. In Santiago we are imprisoned and put on the parrilla. In Buenos Aires they insist we accompany them to dinner outside the prison. We are caught, used and banged away again at midnight. On the Western Cape they come for so many of us that even the media notices. But most of us remain hidden. There are few reports of the crimes against us. Fewer readers.

— Susan Hawthorne, Dark Matters: A Novel (2017, p. 52)